American Culture Is Returning to the Old West

The problem is not that there is evil in the world. The problem is that there is good. Because otherwise, who would care?

There have been four (soon to be five) seasons of the TV show Fargo, adapted from the Oscar-winning film written and directed by Joel and Ethan Coen. I am the show’s creator, writer, and primary director. When I pitched my adaptation of the film to executives at FX, I said, “It’s the story of the people we long to be—decent, loyal, kind—versus the people we fear the most: cynical and violent.” I imagined it as a true-crime story that isn’t true, about reluctant heroes rising to face an evil tide.

Explore the January/February 2023 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

This vision of Americans is, of course, a myth.

It is summer 2022, and I am on a road trip with my family from Austin, Texas, to Jackson Hole, Wyoming. States to be visited include New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah. As we cross each state line, my wife asks, “Do I have all my rights here?” The week before our departure, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, making what was a fundamental right contingent on which state a woman happens to be in. So Kyle wants to know, as we enter each state, whether she is a full citizen in this place, or a handmaid. It’s handmaid in two out of five, I tell her. And in one of them, our 15-year-old daughter could be forced to have a baby if she were raped.

On May 16, 1986, David and Doris Young entered an elementary school in Cokeville, Wyoming. They carried semiautomatic weapons and a homemade gasoline bomb. David had spent the previous few years working on a philosophical treatise he called “Zero Equals Infinity.” This is how it is with a certain type of American male. They start with Nietzsche. They end with carnage.

David had devised a plan to hold each of the school’s 136 children hostage for $2 million apiece. It wasn’t a well-thought-out plan, as David was not exactly a sane man. He rounded up all the kids and handed the bomb’s detonator to his wife, then excused himself and went to the bathroom. Moments later, he heard the explosion. His wife had ignited the device accidentally, bursting into flames. Horrified, the children fled the building.

David found his wife writhing in agony on the classroom floor. He shot her in the head, then turned the gun on himself.

So much for the big ideas of small men.

We stopped for gas in Cokeville on our way north. Rising through the West, we experienced what a philosopher might call reality. The physical world: sagebrush and junkyards, dry streambeds and buttes. The sulfur baths of Pagosa Springs, the road-running groundhogs of eastern Utah. Fewer Donald Trump signs than I’d expected, but more poverty. Abandoned homes and businesses, piles of rusted metal. We saw that each state is in fact multiple states; southeastern New Mexico looks nothing like northwestern New Mexico.

As we drove, we streamed music and listened to podcasts. Texts, emails, and news alerts pinged my phone. In the back seat, my daughter Snapchatted with her friends. It is said that one cannot be in two places at once, but there we were, our bodies moving in tandem through physical America as our minds journeyed alone through a virtual land, one born in a computer lab decades ago: Internet America. This virtual nation is arguably more real to most Americans than all the stop signs, livestock, and boarded-up storefronts.

Internet America is the place where our myths become dogma.

Let me ask you something. When you see a cardboard cutout of Donald Trump’s head on Rambo’s body, do you think, Why Rambo?

I tell you the story of David and Doris Young not because it is remarkable—maybe it used to be, in the 1980s and ’90s, but not anymore. I tell it to you because this figure, the violent outsider driven by extremist views and hate-filled philosophies, is everywhere now. Incel spree-killers and race-war propagators. Young white men radicalized and weaponized. They are the children of the Unabomber, each with his own self-aggrandizing manifesto. They live not in Albany, Pittsburgh, or Spokane, but in the closed information loop of Internet America, a mirror universe that reflects their own grievances back at them.

Their actions may seem irrational, but they are the practical application of a political philosophy. A decades-long undertaking to remake America, to reverse what most would call progress—toward equal rights, better schools, curbs on fraud and pollution, everything our society has done to create a safer and more caring nation—and return it to the way it was in the 19th century. A savage frontier where the strong survive and the weak surrender.

In a hotel lobby in Big Spring, Texas, my daughter and son watch the police arrest a young man for strangling his girlfriend. She is carried out on a stretcher. It has been 36 hours since Roe v. Wade was overturned.

I think about the power of myth often. Though the series poses as “a true story,” each season of Fargo is designed as a modern myth, a tall tale of midwestern crime. On-screen, myths are created not just through story action, but through everything from lens choice to costume. Picture the black suits and skinny ties of Reservoir Dogs. Or the Willy Loman raincoat worn by the criminal mastermind V. M. Varga, the antagonist of Fargo’s third season, a sad disguise he has chosen in order to make himself appear pathetic, easily overlooked in a crowd.

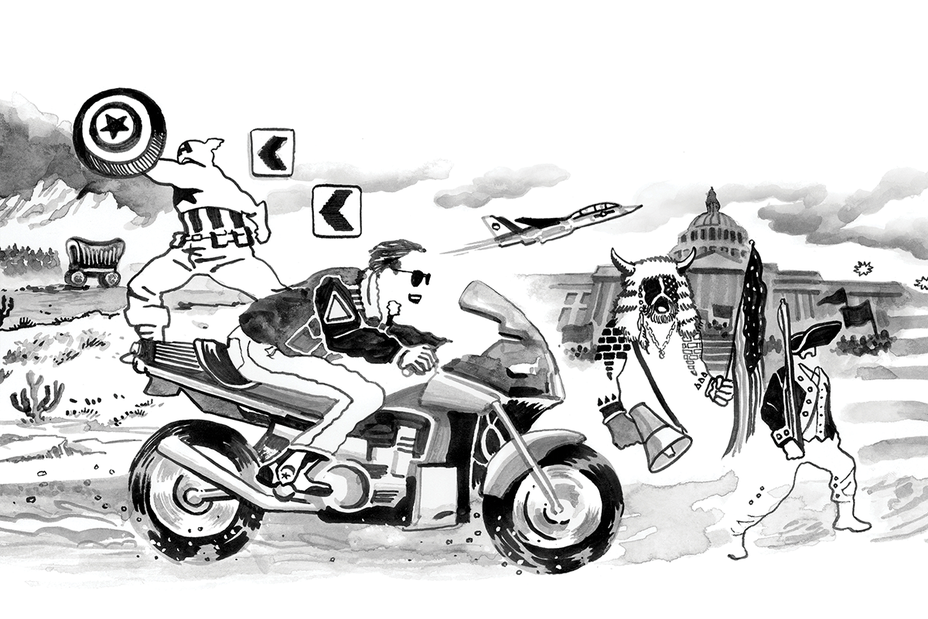

No myth has a greater hold over the American imagination than the Myth of the Reluctant Hero. He is John Wayne, Gary Cooper, Clint Eastwood. He is John Wick, Jack Reacher, Captain America. A man who tries to live a peaceful life until the world forces him into violence. He is John Dutton, the noble rancher in the show Yellowstone, who will murder just about anyone to preserve his way of life, to protect his family and his land. The violence is not his choice, you understand. It is thrust upon him by the demon-tongued forces of progress, modernity, and greed. But he is prepared. And in the end, he is capable of far greater brutality than his enemy.

This is why Trump’s face is on Rambo’s body. Who was Rambo if not a reluctant hero trying to live a life of peace? But the system—small-town cops with their rules and laws—wouldn’t leave him alone. So he did what he had to do, which was destroy the system that oppressed him.

This is how a man must be, the myth tells us: interested in peace, but built for war.

As we enter Colorado, Kyle and I discover an inverse correlation between vehicles that display the American flag and vehicles that follow the rules of the road. As if the performance of patriotism frees one from responsibility, not just to the law, but to other people. Cruise control set, we wince as decorative patriots speed past us, tailgating slower vehicles and veering wildly from lane to lane.

It makes me think of a line from Sebastian Junger, who wrote, “The idea that we can enjoy the benefits of society while owing nothing in return is literally infantile. Only children owe nothing.”

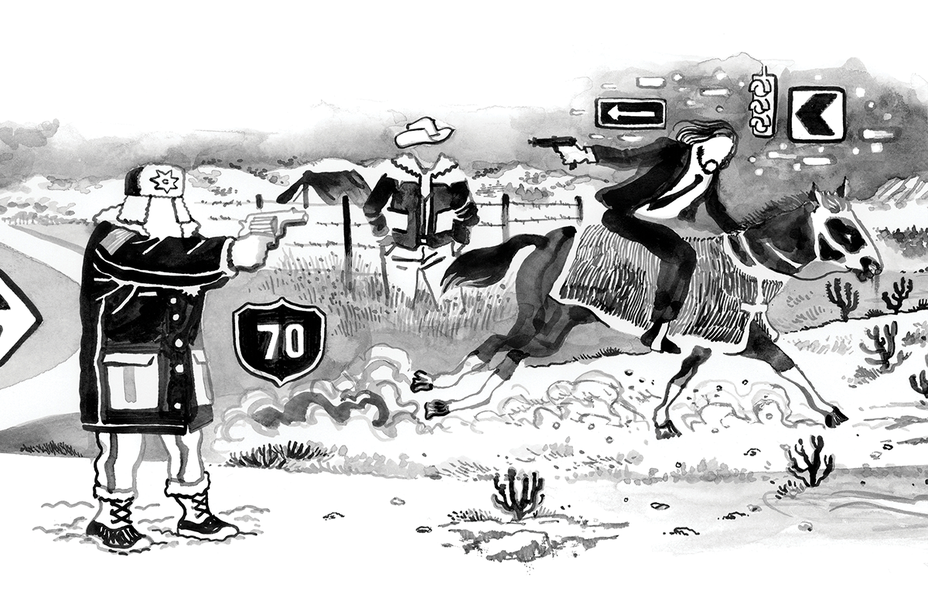

The clearest visual representation of the struggle between good and evil is the white hat and the black hat.

Symbols from the heyday of the Hollywood Western, the white hat and the black hat create a gravity well that storytellers struggle to escape even now. Specifically, the expectation that every story must have a hero and a villain, and that at the end the hero must face the villain in a gunfight (literal or metaphorical) that results in death. High noon is coming, we’re told, a final showdown that will settle things once and for all. Only in this way can the story be resolved: The good guy with a gun kills the bad guy with a gun.

This is not how real life works. Nor is it how the film Fargo works. When Jerry Lundegaard (William H. Macy) is arrested at the end, Chief Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand) is not there. Lundegaard has fled the state, is out of her jurisdiction. The viewer is thus robbed of that crucial showdown—of the hero vanquishing the villain—a choice that felt unsatisfying to some. What you saw instead was actual justice, a system at work, delivering consequences efficiently yet impersonally.

The reluctant hero is noble. He is capable of collaboration, but happier on his own. He is every cop told to drop the case who refuses to quit.

I have created these characters myself. In the first three seasons of Fargo, each of my tenacious if agreeable deputies finds him- or herself at odds with the police force writ large. Molly Solverson; her father, Lou; and Gloria Burgle—each must go it alone (or with the help of a partner) to solve the case and bring the forces of darkness to justice.

It is a seductive premise, the idea of the individual versus the state. Writers as different as Franz Kafka and Tom Clancy have made a career of it. But this year on Fargo I feel compelled to champion the system of justice, not the exploits of a single person—to spotlight the collective efforts of a team of hardworking public servants putting in the hours, solving the cases, bringing the wicked to account. In the real world this is how the peace is kept, how rules and laws are written and enforced.

Here’s an exchange from the next season of Fargo:

Gator: “I swear to God, him versus me, man to man, and I’d wipe the floor with him.”

Roy: “What, like high noon? That only happens in the movies, son. In real life they slit your throat while you’re waiting for the light to change.”

The moral of the Myth of the Reluctant Hero is always the same: If you want real justice, you have to get it yourself.

There is a name for this form of justice. It is called frontier justice. And it’s an idea worth exploring, because we are all of us being dragged back to the frontier, whether we like it or not.

But first it’s worth noting who had rights and who didn’t in frontier times. We can do it quickly, because the list is short.

White men had rights. That is all.

In July, Trump gave a speech addressing the America First Policy Institute, in which he described in great detail what the new frontier looks like. “There’s never been a time like this,” he said. “Our streets are riddled with needles and soaked with the blood of innocent victims. Many of our once-great cities, from New York to Chicago to L.A., where the middle class used to flock to live the American dream, are now war zones, literal war zones. Every day there are stabbings, rapes, murders, and violent assaults of every kind imaginable. Bloody turf wars rage without mercy.”

The belief that America has become a hell on Earth—“a cesspool of crime,” in Trump’s words—is rampant on the new frontier. The people who believe it, the New Frontiersmen, used to live on the fringes of American life, but not anymore. They are citizens of Internet America who do their own research, who believe that something vital has been not just lost but stolen. In their minds, the 2020 election was only the latest in an ever more audacious scheme to disenfranchise and disrespect the hardest-working Americans.

Have you ever noticed that in stories of the zombie apocalypse, such as The Walking Dead, the real enemy is always other people? This is not an accident. It is a worldview rooted in the belief that, were the rules of civility to fall away, your neighbor would just as soon kill you as lend a hand. This is a core belief of the New Frontiersman.

In December 2016, when The New York Times looked at where The Walking Dead was most popular in the United States, it found its fan base concentrated in rural areas and states like Kentucky and Texas, which had voted for Trump. It makes a certain amount of sense. If you’re convinced that the world is intrinsically uncivilized, you will gravitate to stories that agree with you: wish-fulfillment fantasies where neighbor can kill neighbor.

If this is how you see the world, then the laws of civilization—laws that would force you to surrender your arms and join the rest of the sheep—must feel like madness. You might even begin to suspect that the sheep telling you not to fear the wolf is in fact a wolf himself.

The New Frontiersman believes that only a good guy with a gun can stop a bad guy with a gun. In his mind, he is that good guy.

Another name for frontier justice is vigilante justice. The words have a long, ugly history in America, evoking images of the lynch mob. But they are modern words too. Hollywood is full of stories of vigilante justice. Batman is a vigilante; so is the latest Joker. Vigilante stories offer a romanticized vision of violent men who live in darkness, fighting to protect the rest of us from the evils of the world. They do the dirty work the rest of us are too scared or too weak to do. This is another myth.

In 2021, we were introduced to the oxymoronic idea of vigilante law. In Texas, S.B. 8 was approved by the legislature and signed into law by the governor. The law deputizes citizens to sue anyone who helps a woman get an abortion. It has been allowed to continue unchallenged by the Supreme Court, which seemed to suggest there was nothing our 246-year-old democracy could do to combat the will of the mob.

There is no named enemy in Top Gun: Maverick, the summer blockbuster playing at every American multiplex we pass on our drive. No Arab state or resurgent Cold War foe. Instead, the enemy is the rules themselves and the bureaucrats who enforce them. Navy brass with their flight floors and ceilings, their by-the-book mentality. Only a maverick can save us, the film tells us, not just from foreign threats, but from the system itself.

Top Gun’s motto is “Don’t think. Just do.” Instincts, not reason, are a real man’s strengths. Thinking loses the battle. The things a man knows cannot be improved by innovation or progress.

Here myth and reality separate, because in the real world, “Don’t think. Just do” is not a governing philosophy. Do what for whom? What if different groups want different things?

But to ask such questions is pointless in the face of a worldview that dismisses the very idea of questions. “Don’t think. Just do” harkens back to an older American motto: “Shoot first. Ask questions later.”

On the road trip, we listen to Lyle Lovett. We listen to Willie Nelson. Hayes Carll sings a song about God coming to Earth that ends with the refrain “This is why y’all can’t have nice things,” and I find myself tearing up. I’ve got a 9-year-old boy and a 15-year-old girl in the back seat of the car, and I don’t know how to prepare them for a world in which half of the citizens of their country already appear to be living in the zombie apocalypse, armed to the teeth and fighting for survival. The zombies they’re aiming at are the other half of the country, still very much alive and struggling to understand.

Myths endure because they’re simple. The real world rarely offers up important choices that are binary: black hat or white hat. I think of Fargo as many moving pieces on a collision course. Which pieces will collide and when is never clear. Randomness, coincidence, synchronicity—all are available to me as I attempt to capture something resembling the complexity of life.

Here’s another way I describe Fargo: a tragedy with a happy ending. Tragedy in Fargo is always based on an inability to communicate, sometimes even with ourselves. People are like this. We avoid difficult subjects.

As in life, everyone in the stories I tell has their own perspective, their own experience. The more selfish they are—the less able they are to accept that other people’s needs matter too—the worse they act. I’m the victim here, they shout, as they impose their will on others.

What was the QAnon Shaman if not a creature of the frontier? How many versions of him did we see on January 6, dressed in colonial or Revolutionary War garb? It’s no accident that the cosplay insurrection drew from early American iconography. It was a throwback to the era when white men battled their way through what they saw as an uncivilized nation. When the only way to fight the savagery of their enemies was savagely, without mercy.

A tragedy based on an inability to communicate is also a good way to describe the current American predicament. You have two sides that both feel aggrieved. Each believes that their own pain is real and that the other’s is a fantasy.

One side believes the last election was stolen. The other believes the right to vote itself is being taken away.

One side believes that the answer is reform, better government, a truly equitable system of justice. The other believes that government itself is the problem. Both sides are yelling and neither is listening, like a man in a fun-house mirror convinced that his reflection is a stranger.

When communication stops, violence follows. Your opponent becomes your enemy, a black hat to your white, and we all know what happens after that.

The show 1883, created by Taylor Sheridan, who also created Yellowstone, explores the frontier mindset with great sympathy. To quote its young heroine, “The world doesn’t care if you die. It won’t listen to your screams. If you bleed on the ground, the ground will drink it. It doesn’t care that you’re cut.”

From the December 2022 issue: How Taylor Sheridan created America’s most popular TV show

It’s better not to try to make sense of this world, we’re told, after we watch a settler shoot a woman who has been scalped by Natives. The man is hysterical, quite rightly out of his mind with grief and shame at what he has done, but Sam Elliott’s character tells him: “You made a decision. You did what you thought was decent. Was it decent? Who knows. What the hell is decent out here? What’s the gauge? You’re the gauge. You made a decision. Now stand by it! Right or wrong, you fucking stand by it.”

This is frontier morality. The world is inherently indecent. No government law can tell us what is right and what is wrong. It is up to each of us to decide.

If you play it out—one step ahead, two—you realize that the inevitable end point of this new frontier mentality is crime. Because if you privilege what’s “right” over what’s legal—and appoint yourself as the arbiter of right and wrong—then you will inevitably end up in conflict with the rule of law.

In this way, the frontier becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Those who believe in it must create its conditions or become criminals in the civilized world.

The left, of course, has its own myths. The Myth of Stronger Together, the Myth of a Rising Tide Lifts All Boats. We like stories of collective action, stories about unlikely bands of misfits who realize that their differences are what make them strong. Think of the unsung Black women in Hidden Figures, overcoming personal prejudice and institutional racism to help make spaceflight possible. Even our Westerns are pluralistic—think of The Magnificent Seven and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

Stranger Things is a liberal fantasy, all those plucky kids banding together, never leaving a friend behind.

Squid Game is a right-wing fever dream, as if I even have to say it.

Game of Thrones was a Stronger Together Myth posing as a Frontier Justice Myth. For all its rape fantasies, it was at heart a meditation on human nature, a cautionary fable about morality and power. Good was rarely rewarded, but only collective action could save the world.

If you map where Game of Thrones was popular in America, incidentally, it aligns primarily with blue states. It was the anti–Walking Dead.

On the Fourth of July, we gather in a park in downtown Jackson to hear music and watch the fireworks. Earlier in the day, a 21-year-old man shot dozens of people from a rooftop in Highland Park, Illinois, killing seven.

Later, Kyle and I compare notes: how we both noticed the same open window in a nearby building. How we both had a plan for where we would go with the kids if a gunman—no, let’s call him what he is: a terrorist—opened fire on the crowd.

Later still, I learn that a toddler was found alive in Highland Park, lying under the dead bodies of his parents. Is this really the price our children must pay for our inability to come to terms with one another, to communicate?

The next day, when I tell my son the story of the shooting, he asks what we’re going to do about it—we the surviving Americans.

We’re going to buy more guns, I tell him.

0 Comments